The Mute Swan of the Lough

Where you go, there are no others.

They accompany you to where you raise your face into the light,

where the ballroom submerges beneath the lake at dawn.

In the depths, water from the golden vessel washes you

to show there is no difference between the elements.

As time goes by, just the shape changes.

In the end, everything is covered by winged animals.

There are coots and a black swan on top.

Every whir of every bird is a wave of the moment.

The feathers of the sleeping wild ducks gather on my back.

Like the rings of the water next to the ledge

swollen yesterdays are washed up on the shore.

I head off. The sunset passing over the mud is behind me

it swallows the unutterable fragments of words.

In the middle of the lake, the hiding fish decide

not to remember anymore.

If you let it, it will come back to you.

It will be standing at midnight

without any words, being ill at ease

in spite of it having been prepared for months

polishing words like pebbles.

It steps out from the shadow of a doorway

as a tall man with mute keys in his pocket.

The ink which stains from the warmth of his hand

is a shining buoy under the walls on a postcard.

By then you will forget from where you came from and why

you have so much seaweed around your feet.

You watch a couple of mute swans lifting up to the sky

and you don’t understand what kind of strange country they crave for.

Leave cognition and resurrection to others.

Don’t ravel knots. It’s unnecessary.

Watch from the shore how the light bathes on the lake.

Be the light which raises the world’s face.

The Heart of the Hurricane in Cork

It arrived the next day as they foretold.

The rain was drizzling non-stop

as I took pictures of the church with four clocks

for him, to see the reality of every season

of every time.

He doesn’t freeze moments.

His inner shutter locks him up.

The humid calvary

of my face appearing upon his.

It is an unknowable crystal construction.

I am approaching its strangeness,

an iron handrail in a round open-air corridor.

As time goes by it submerges within me

as one does within the endless.

As the ocean’s depths mirror its cliffs

he can’t touch this, can’t taste it

he just contemplates me.

The objet obscuraof his desire

fuming in my unbound hair.

He combs it through from hair to hair,

like mornings comb the forests.

He leaves nothing to shadow,

dismisses delusions, sees them die.

There is silence in the center, I am standing there.

I am looking to where he bends down at the shore,

he finds tiny snails, crayfish in conches,

he walks on guano and seaweed.

Lights up a cigarette and smokes.

I can hear him sitting on the pebbles

how he rumbles and reaches for the clouds

how he brightens around himself

the lazy mainland stretching out.

Every curve of her land is a testimony

as she lets it abrade her

and the trembling earth

flies the moon above her like a kite.

I do not watch him, I don’t want to change him.

Let him be himself with a silent rain in his heart.

The distance lifts me up, I fly into the wind.

Like I let him on Sunday afternoons. Tame me now.

Blarney’s walk

I know neither time nor distance

The tamed light is widening in me

with the tangly breath of the lake

The pier twists because of our footsteps

like the wings of angels before the dawn mass

The dust flying in the golden sunlight

that waits for spring after the winter in my hair

It won’t hurry the rules of nature

it keeps vigil over the dead

and sets off toward the ocean

The sky lifts me up by the arms

A weightless mist snoozing through your fingers

we are rising together, I can see you flying

The lake and sea open as one

Your dream meets my life in the infinite

Shandon Arms

It is called a lying clock but the truth is something else. I come from the street below after reading the name of the street on the wall of the house, Mary’s Lane, Shandon reminds me of Víziváros, Watertown in Budapest. It combines the height and depth of the city with waving stairs, it meanders like another river in Budapest, called the Danube. Here the River Lee does the same with the wide riverbank next to it.

The tower across shows 5.07 p.m. I change my mind and turn right, turn to the garden of the church. The road is next to ancient graves, I see a man with a dog in the garden, there is a married tourist couple on the other side of the park. The face of a woman is glamorous, the purity of her beauty incandescent. The wind is playing with her hair. The famous salmon on the top of the tower shifts around slowly as the wind moves, it looks like it lurks after the woman between the lights of the park.

The boy arrives at the coffee shop hugging his arms around the wooden crate box, he puts the carefully sorted wildflowers into the little brown vase next to my tea. The mug is meaningful, the last time it was illustrated with a young man holding a pen, this time there is a monk on it. He cuts the bush and a young woman is standing behind him with dreamy eyes. I go off to Saint Anne’s church next to the pub called Shandon Arms. It is closed, there is a sentence on the door: ’You can buy beer, wine, tobacco and ghosts’. I turn back to check the time, 10.47 p.m. and I can also see another side, where reality shows 9.56 p.m.

The church is full of people but I enter because I promised that I would take pictures of the inner world. I have to push the door hard like I’ve made a decision without any hesitation. The door closes slowly, as if it loved more to let people and things in, than out. The one inside is not urged to do things, he lives that moment of time in a different way.

Because of the surprise I don’t know what I am feeling but at that moment the mass is getting started as I enter the church. On my arrival the inside crowd stand up all at once. Quickly I sit down on the nearest seat. There is a man behind me, beside a woman in a red coat. The minister starts to talk. I recognise the meaning behind the English words, which are shocking to me. They are listing all the sins. Who knows what’s happening? Even though the sky is up high, there is no dome, just the four towers, but I feel as the tears fill up my eyes,that even by thoughts, by words, by acts orby missing things, it is still not clear what touches me from what they say. My heart is noisy, but it was cold out there. The wind is blowing heavily, the slow movement of the salmon keeps going on within me, swimming as if it were in a way to get home, instead of finding its way to the ocean.

The polished parquet block mirrors the light. The columns are decorated with bamboo all the way around, I see mostly white colour and wood in the church, there is no gold shining like at home. Everything is simpler. The old people with grey hair, their hunched backs, mostly covered by quilted jackets. There are only a few sharp colours. It is warm outside but they know it can rain anytime. This knowledge makes me amazed, here the diversity of life looks as if it is breathing a concentrated air, Ireland is gasping, maybe it feels the end, I don’t know what causes the exaggeration, what is behind it, fear or something else. I feel the same power seeing sandals on people’s feet in autumn and seeing the strong make-up and tattoos on women’s faces, meeting the swallowed words of silent men, tasting the strong and coffee-flavoured beer. The staff are loud, they address you, you cannot walk next to things because they ask you to pay attention, in spite of your answer they refer back. And they keep smiling. They don’t hurt you. The eyes of men don’t hurt you and neither do the opened laps of women walking along the streets in the evenings, in spite of grabbing tourist men’s hair, in spite of pinching men’s faces, men have their free will about how they want to keep on. The openness and spaciousness are the same as below with the salmon, in the deep, mossy green ocean. People in Ireland change the world around them like the salmon does on the top of the tower, not to be lazy on rainy weekdays. And if they ever forget it, the tourists from other countries will remind them how they love to live. Lesson learned.

I was right here, in this church some weeks ago. It was a different Friday morning after the mess and I was alone, except for a man. Jesus was missing from above the Lord’s table, but actually, that’s not the truth. Jesus didn’t get off the cross, he crucified himself on the colours. It started with turquoise, then he submerged into navy blue, and later his painted red glass body. But I hadn’t seen that yet.

There were only the lights pouring across the walls, as all these colours were flowing into each other, together and apart, decorating the hard blocks of the church. As turquoize was blending with yellow my dream came to mind. I was walking on the riverbank on the way to the Opera, meanwhile, you were crossing the River Lee with a skateboard. Lights moved in and through each other, redrawing the way of Jesus, threading the resurrection with colours.

I remember the thick light in my throat, I could not speak in a foreign language, I had fear and strangeness in my stomach. In spite of understanding what people said, and knowing what I wanted to answer, there was only silence. The habit of fear is an inflexible frame. Instantly, as the frame starts melting, the tightness in my throat becomes loose, and I can breathe again.

I found a little card next to the sculpture, the prayer of Saint Francis of Assisi. I didn’t remember the meaning of the word ’serenity’. While I was reading the prayer about patience, bravery and wisdom the salmon started to creak – it could have been waiting for this sign.

The last sculpture is on the right hand side of the church. Mary with Jesus after the crucifixion. I am thinking about this a lot nowadays. Starting with the angel as it arrives, soto whether and what it means to be chosen. What if everything I have, everything that happens to me wanted to be mine? How will my life change if I know and feel and see that everything I live for is fullfillment? In this way, there is no desire because desire is only one part of me. It doesn’t matter what the time is because the clock goes round, and the clockwises reach me in my soul, I am the clock face also.

So, if Mary knew what was to happen to her and her son, if Jesus knew and Maria Magdalena knew too, what kind of soul could put them up to saying yes? After the disappointment, hesitation and pain how could they find any belief and strength inside?

I see you in the rain. A whole day of chasing behind you. Calls, arrangements, tasks, neverending lists, and the sky falls down. There is a red Volkswagen in front of you, a green Renault behind. Although you are a good driver and they drive well, too, in the next moment you can see only the curtain of rain and you hear the bang, your body shoots ahead, the belt keeps you safe, the cell phone falls down, your neck jerks back. There is no time to remember which one is first: fear or anger. You are still alive. Voices become silent, you jump out from the car, run to the others, everybody is safe. You stop. The cars pass you by, you are in the middle of a space that looks as if it has opened by itself. Your clothes are really wet, you throw your jacket, t-shirt, trousers, stockings, and shoes away. But now you are just standing, standing in the rain, you breathe in deep and after the panic a perfect calm flushes through you, it is a spicy silence and that’s all, you are alive, it doesn’t matter what the time is, the windscreen is still working, it looks like a metronome, a time-keeper measuring your pulse, you are getting silent, you are not grasping. You have a clock inside yourself, too. It doesn’t matter where you hurry to, what urges you, if you escape or you are pursued, you can not be faster than yourself, Shandon arms keep you strong, they hug you like the clock face hugs in clockwise.

Clean sheet

I live by the sea.

There the heart halts ever more slowly,

Gulls drift onto seaweed and jellyfish.

But I’ve drawn the curtains on the room,

I didn’t want to see the sunrise.

The flaking plaster will stand in its place,

On the water opposite, as the sun looks into my eyes.

This season is a slow one for death.

Someone inside me beats a clapper,

But the bells ring distant.

Look at the shore. I can remember, how I’d jog out every morning,

Wanting to believe it’s not so deep.

And the low-tide would help me lie,

Such a load of questions left unanswered,

But before the end I’m searching the word for high-tide.

This strip of coast is a hollow echoing bell,

The curtain is quite the opposite:

It can never hide the room.

Long shadows like exclamation points,

the waves are hauling something.

Like the sound of seagulls in the morning,

unbearably beautiful.

Now then come closer:

this here’s my bed.

So many hearts were here yet now it’s empty, like a lake.

Were it salty you could call it sea,

But I haven’t any tears to hold back.

I loved too. And there’s always the present tense,

But isn’t this human side ridiculously touching.

Don’t take me seriously.

Just look at my bed.

The salt dried onto the frame.

Like flaking plaster, dropping leaves or snow,

All who wish to see it burn away.

At least God could lie a little,

Saying the Monsoon actually exists.

(Owen Good)

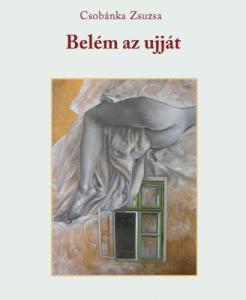

Reminiscent of Woolf’s “The Waves” yet unmistakably Hungarian in its depiction of the post-socialist heritage, “Fingering Me” is a collection of short story-like vignettes or diary entries, told alternately by a male and a female narrator.

Zsuzsa Csobánka is primarily known in contemporary Hungarian literature as a poet, and her two volumes of poetry (Bog [Knot], 2009, and Hideg bűnök [Cold Sins], 2011) have been widely praised for their objective tone and the intense metaphorical depiction of bodily experiences. The publication of her first work of fiction, Fingering Me, in 2011 marks a new phase in her oeuvre in terms of genre, but it is also deeply rooted in the author’s previous poetical output. Although the somatic discourse on eroticism and death are not absent from contemporary Hungarian literature (Attila Bartis and Krisztina Tóth even appear on the back cover of the volume, but Márió Z. Nemes, Endre Kukorelly or “Laura Spiegelmann” – the pseudonym of a supposedly male author – are also key representatives of this visceral tone); the female perspective on these issues is a relatively recent phenomenon (with Edina Tallér’s A húsevő [“The Carnivore”, 2010], Zsófia Bán’s Amikor még csak az állatok éltek [“When There Were Only Animals”, 2012] or Noémi Kiss’ Ikeranya [“Twin Mother”, 2013]). The vivid reception of Csobánka’s novel indicates that the text has challenged both the genre criteria of the novel and the controversial notion of the feminine mode of writing.

Fingering Me is a markedly lyrical collection of short story-like vignettes or diary entries, narrated alternately by a male and a female narrator, the ex-lovers called Martin and Marla. All the other characters are somehow connected to this past romance (with Martin’s [grand?]mother as the most finely delineated among them), as the web-like family tree at the end of the novel shows. Considered an ironical gesture by many critics, the family tree can be read as an allusion to One Hundred Years of Solitude or, on a more general level, the metaphor of intangibly complex human relationships. The story is narrated along metaphorical and associative rather than logical lines, which makes it difficult, if not impossible, to sum up the plot. The book reads like a loosely connected series of dramatic monologues, linked by the motifs of blood, wound, heart, yarn and flesh. The topics of abandonment, sexual initiation, old age, death and transgression keep recurring in both narrators’ chapters, shedding light on different, often gendered aspects of these experiences. The alternating voices of Marla and Martin can also be read as a mourning process, verbalizing the bodily memories and emotional turmoil of the death of love. The lyrical voice and the metaphorical junctures provide a textual rhythm, as in The Waves by Virginia Woolf. Yet the book is unmistakably a Hungarian one, with its depiction of rural and urban Eastern European settings, and the bleakness of the post-socialist heritage.

Fingering Me, a book which is unique in contemporary Hungarian fiction, reminds the reader of works by authors like Elfriede Jelinek, Denis Robert or Angela Carter. From Woolf’s stream of consciousness to Hélène Cixous’ écriture feminine and the often traumatic inscriptions of eroticism in fiction, Csobánka’s book invites various modes of reading. An English edition would open up a fertile dialogue between contemporary Hungarian literature and the various literatures written in English, with special regard to the depiction of women’s experience and embodiment as such – two highly contested thematic and theoretical issues of cultural studies today. Zsuzsa Csobánka can be rightfully called the pioneer of this tendency in our literature, creating a new idiom of embodiment and eroticism, as she herself puts it in an ars poetica-like statement: “There is no sober language of sexuality between pornography and pathology.”

Madonna

Cika Madonna was bolstered up by my Mumsy. She was a tiny woman with deep ditches of wrinkles running all over her body, I saw it when my Mumsy nodded towards a big heap of clothes, ‘You can take any of these that fits.’ Cika Madonna walked slowly to the heap, and like a suspicious rat, she sniffled around the combies, dressing-gowns, sweaters. ‘I don’t wear them anyway,’ my Mumsy said, and cast a meaningful look at Cika Madonna’s naked ankle, its veins bulging under the coat of dirt. Her nails were thick and horny because she usually went barefoot’d, Mumsy only let me do that in the summer, ‘You have to be beautiful, my son, women don’t like sloppy men.’ I hadn’t seen gnarled feet before and Cika Madonna was the first woman to show me her breasts, too, while hastily tumbling into my Mumsy’s flowery blouses.

She didn’t speak much, everyone knew it anyway that she used to go to the carrion pit for dead cats, hedgehogs, when there was no one at all to take pity on her. Always at the end of the month, and at the beginning of the year. We once peeped at her with Rudi. For a week, we would hide behind the hedging in front of her shed every morning, waiting for her to go for a hunt. My Mumsy gave me a helluva smack afterwards, she must have smelt where I’d been. The carrion pit was at least a ten-minute walk, and on top of that, there was hardly any hiding. Rudi was just about to turn back because Cika Madonna kept stopping and we thought she must have spotted us, but she just dug her nails into her downy hair. ‘Watch out, my son, women also go bald, but with them it’s not their foreheads rising, but the hair grows ever thinner, and in the end it just gets humiliating and pointless to dig into it, because every time a mop stays among the combs of your fingers, as if they were sunshades against the shining scalp.’ Thus, as long as I could, I just watched them shaking their hair, running their fingers through it, since they could only do so for some time. While others were taking snapshots of hollow bellies, bulging breasts or round hips, I had dozens of secret photos of women tossing their hair. The image of course was only a fragment of the movement, it didn’t have anything to do with life, but those pictures still staggered me when I came across them years later. Rough hair with broken ends, unkempt and greasy, but still, these were the women who once drove me mad.

Her arms were covered with bruises, hedgehogs were aggressive, but still weaker than Cika Madonna. When she turned up in the village, people whispered behind her back and withdrew into their houses. She trusted holiday-makers like Mumsy, who might forget the begging in a year’s time. They were relieved to leave marks in the untouched, virgin snow in the winter, seeing that no one had broken in that year either. We were driven out of the city by the heat only, actually, it was easier to bear it there, but Cika Madonna didn’t know this. Only Mumsy and me knew that Astoria and the Western Railway Station knew nothing about poverty, and the Madonna about begging either, since what she did was simply sitting down on the dusty dirt road in front of the houses, singing songs and waiting for us to wake up.

‘Give me your shoulder,’ the Madonna told me, I was afraid if she had really seen me, and might decide to revenge the peepers, leave without the stockings and shoes, and tell Mumsy everything. But she only needed my shoulder to lean on something. You see, Marla, that’s what you’re all like, you women. She only needed me for taking her slouching pumps on. My first lover dropped me after I’d been caressing the rape out of her for half a year. She couldn’t even be touched at first, only with words, that’s when I became the master of sentences, I took it to perfection, which verb fits which noun, what kind of exaggerations, adjectives I am to pile up so that she opens her thighs at last. And you know, Marla, once I managed to put my dick into a raped woman, I thought to myself that there was no impossible thing in this world. And then came the other one, Gertrude. By that time I had sworn to God she wouldn’t let herself. Gertrude was older than me, a bony woman and afraid in the dark at night. I lived at her place for two years. Board and lodging in turn for talking to her, she said. I had been living there for almost a year when one night she fled to my room from the banging storm and cried out, ‘I saw a miracle’. I broke out laughing loudly, and then Gertrude, to prove her point, knelt down by my bed, took all my toes into her mouth, one by one, she rattled and cried, then went silent and sucked me. This made me remember neat men’s feet and what Mumsy told me about not being sloppy. I wondered if she liked to take them into her mouth, too, and maybe that’s why she had warned me.

This is what I saw, Marla, as I reached for your feet. Your hands are real maiden’s hands, I said to myself. I say, I can talk anyone into bed, if I have to, and you were no exception, don’t you think that. You are so alike, you, women. I was sitting on the edge of your bed, grasping your feet, and later the shrieking hedgehogs came to my mind while I was licking you, I say, it was the very same frequency that Cika Madonna had wrought out of them. She was hitting the ground with a knife tied onto a long rod, from a distance one could think she had no idea what she was doing. Blood was spurting everywhere, ‘There are more of them,’ Rudi whispered aside, and I was nodding, because one hedgehog couldn’t have possibly made all that noise. While she was skinning the animals, Cika Madonna’s face got all bloody, her arm covered in bruises. We heard her cursing aloud, the jumping fleas might have bitten her face as well, they sprang into her mouth, her nose.

It was there and then that I learnt the most about women, that the Madonna is a bitch, with bugs and insects dwelling in her orifices. Then she staggered, lost her balance while she was changing her skirt, and a raw, sour smell hit me from between her legs. Mosquitoes flew out. My Mumsy warned me not to gaze, but I was only looking at the filmy membrane of their wings. They were fluffy and shiny, just like the Madonna’s hair. The skin above the skull was white, white as the hedgehogs were when she skinned them. There might be something white and colourless about death. It was death, when I gripped your thighs, and everything got blurred. My face is all bloody all, I curse aloud while the bugs are biting me. Rudi is calling out, ‘Let’s go,’ but I don’t move, I’m just watching the Madonna’s mouth moving, and while peeling the thorny skin off, she’s singing.

Mumsy dies

The bundle was quite heavy, she slowered her steps and was panting for breath. Mumsy felt uncomfortable, she wasn’t even consoled by the fact that she deeply believed in what she was just about to do. The weekend houses were all silent, well after the end of the season the town was abandoned. In the gardens, she still saw unfinished sand castles here and there and a flat collapsible boat. Maybe it’s punctured, that’s why it hasn’t been stolen. Swallows were sitting on the wires, they made a terrible noise while settling on the line at equal distances, egging on each other, then they all flew up, made a circle, and sat back to their places where their companions were waiting for their turns. The bundle was silent, too, she knew it wasn’t normal either, however, noises would have been even worse. She would have told herself, ‘I must be hallucinating, nothing can filter out of this.’ At the end of the street she stopped. She didn’t even admit it to herself, but she needed a break before reaching the river. It was called a river, but of course it was hardly a few inches, sometimes only ankle-deep. When she was a child they often cooled their heated bodies in it, later she used to bring Martin here so that he sees other women’s thighs, too, not only hers. ‘Mumsy, I’m really fed up,’ she remembered this very well, Martin wanted more and more every week, after the bathing suits there had to be girls in bikinis, tongs, topless and then he demanded nudists. ‘Martin, you’re hopeless, don’t you ever marry, my son,’ she told him, but Martin just broke out laughing, ‘But how will you have grandkids then, Mumsy?’ he asked back. Mumsy went silent, Martin’s father came to her mind and such commonplaces as blood is thicker than water and that those chasing cunts as a kid would never get settled later either. ‘Mumsy, I’m fed up,’ he would say, ‘I’ve already returned Edina’s keys.’ Mumsy would be eternal, ‘I’ll only love you, Mumsy, till I die,’ Martin shouts, and pulls his mother onto himself, and Mumsy is actually happy, she is at her happiest now.

She’s thinking about this while she’s picking her way, where is this sentence gone, where does the wind carry all the confessions, promises, how impossibly far Martin from her now is, she has no chance at all to change anything. Maybe the bundle. The water is surrounded by thorny weeds, she’s hesitating for a moment whether she really wants this. She doesn’t sit down as she planned, she just loosens the knot at the mouth of the sack. The humidity hits her face, she curses in desperation because she feels that she’s weak after all. She doesn’t dare to open it wider for fear that they might instinctively crawl out and she might even have to chase them around then. Her mother used to call this “just taming them” – I’m taming the little pets, look, you pick the skin right at the neck, it makes them freeze because they think they’re between their mother’s teeth. It’s easy afterwards. It doesn’t move, doesn’t make any noise, and so it is barely alive. An object, lifeless, like throwing a stone far away. The child Mumsy raises her brows. ‘Are you being distrustful, you bitch?’, her mother asked, and pinched her face. It hurt, she always began to hate her at this point. It was an old game of theirs, mummy pinched, Mumsy gasped. Like the kittens in the sack fifty years later, as Mumsy leans over them. ‘It might be easier if I name them.’

She addresses the first one as Leila, ‘Come, kitten Leila, I’ll tame you.’ She gets it by the neck, but it doesn’t work out at first, the animal doesn’t freeze but is kicking nervously. The whining makes Mumsy upset, she pinches the skin tighter at the neck and succeeds this time. The cat goes silent, lets go of its legs, the body is hanging languidly. It doesn’t move, doesn’t make any noise, and so it is barely alive. From her hip, she turns towards the river and tosses the cat in. ‘Fly, kitten Leila, fly.’ I don’t want to remember the blonde curls, waiting for you in front of Centrum, the pub where you sat down next to me. Damn you, kitten.

She starts to hum for the second one, ‘Anna, Anna, Anna.’ The animal smells danger, and feeling Mumsy’s rage, wants to pull away. Anybody watching this would have looked away, it’s not a sight for humans, as with the kitten in hand, Mumsy is slowly undressing, down to her combie. ‘We should tell at the grocer’s,’ the bushes whisper, and in the bush the six- and seven-year-old sons of Feri, the neighbour. But neither Gabor, nor Mark has ever seen a woman’s body before, their mother is shy, keeps hiding herself day and night as if she were hiding a treasure. Her legs are thin, only her belly swells disproportionally, and it wasn’t even because of the boys, the neighbouring woman used to say that she is carrying too many burdens, and she cannot shit it out and that she should only tell Feri once, ‘my dear Feri, it just won’t do for me,’ however, the shit is only accumulating in her belly, getting ever bigger. Those who don’t know her think that she’s pregnant, a layer of skin upon the barrel of fat or water, with no bum at all to balance it. Mumsy stops, the combie is fluttering, curling in the wind, Gabor and Mark are feeling something strange, their breathing fastens, they don’t know what this is.

Mumsy now raises her arm, ‘Dance,’ Martin says, ‘Dance, Mumsy,’ but it’s another image now, the room is humid, Martin is getting married, he’s happy, only Mumsy is out of breath, too much fag and guests, stop it, Mumsy, your only son is getting married! Mumsy stops, snaps her hand, ‘Don’t you dare to order me about or haul me up for anything, my son, anymore,’ and rushes away, Martin is standing there, still hearing Mumsy’s hissing, even though all is silent now, only the wedding band is playing, but that doesn’t matter. ‘Swing-swang, kitten Anna, fly away,’ swing-swang, and it sinks into a deep sleep. Gabor and Mark are terrified, they didn’t see what this neighbour in combies got in her hand, they only see it after the splash, because Mumsy misses the direction and kitten Anna hits against a rock. It doesn’t move, doesn’t make any noise, and so it is barely alive.

The bundle is silent, ‘Cathy, kitty-cat,’ she’s fondling it daintily, ‘your back breaks, I’ll crash your skull,’ she’s singing in a drowned voice, and the two kids cannot even move, the bigger is feeling nauseous, though, and the smaller one has wet himself. They are afraid and cursing the minute they slipped away after lunch, ‘My God, good God,’ the bigger one can only think of this, and the smaller is murmuring to himself, ‘I promise I’d be good, I promise, I just want my Mummy.’ In the meantime, he’s keeping his eyes tightly shut. Mumsy is naked now, the hair between her legs is grey, she digs into it with her left hand, rubbing it, grasping her breasts as if she could carry their weight. Her face is wet, Martin had left me, ‘Don’t you dare, my son, to bring any more women to me, and this Kate, I swear to God, I’ll crush her, gut her and curse her till my mouth bleeds, because there’s no fucking such women for you, son, no, there is no such thing that I cannot tame these little pets.’ With the third she gets her hands wet. In the summer the water reaches up to her ankles, but it only touches her wrists now, there is no flow, the water keeps the body down. It could still be warm if she put it out onto the dry, but this one is wet already, cold, and that’s how it has frozen, whether she pinches it at the neck or elsewhere.

Mumsy is dreaming. She’s finished with the lil’unes, she has enclosed them into themselves. To tame is to let close. Not moving, not making any noise. Just watch it getting closer.

Passing right now

Me Mumsy, I’m burying Marla today. The most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen, the most beautiful woman to whom I’ve lied the most, as if to myself. But Szofka is irreplaceable. Because Szofka is earth and mud, too, do forgive me, ‘cause Szofka is belief and disgrace, too, do forgive me. Because God had sewn Szofka’s hair into my shirt, me Mumsy, you had taught me this, even if Edina’s face got swelled, even if I leant on the wheel that afternoon, life is only Szofka. Without Szofka there is no Marla either, but without Marla, everything is just there, everything is a lot better, now that there is no Marla. When I hit her for the first time, you came to my mind, how we always hit because of a woman, we, men, me Dadsy, you forgot to message me this, and now from beyond the grave you’re telling me in vain. Grandpa knew, he told me, ‘Listen, Martin, you also need some spice for life, the fuzzy lap of almond-eyed women that drive you crazy, because you’d be homesick even there.’ Szofka knows this, you’ve made the right choice, she’s gasping for her breath, waiting, ‘Don’t you hurry, you’ll soothe her, because her heart gets tired sooner, while you’re leaning against the wheel that Autumn afternoon, she’s preparing herself already.’

Edina is long dead. Don’t you care about the swells, even if the constat says it would take more than eight days, you are already elsewhere. Never where you should be, Grandpa, to be happy is to be on the road. ‘No, Martin, you are simply a coward. A coward to live and a coward to die, you’re digging the earth so a woman can fill your mouth with mud afterwards. There is only one woman like that in the world, and she is filling herself with mud in you, and you’re stammering in vain for forgiveness. You think that Szofka forgives you, but it’s you who cannot forgive yourself.’

Me Mumsy, I’m burying Marla. Grandpa says I should be honest and fair with her at least in my heart now, but I don’t understand what he means. Because Marla is dead. I should write about her nails, because they are still growing, and her hair, she used to dye it, the redheaded bitch, I’ll tell you, that’s what she was. At last she showed her true colours. ‘Now even your photos look pitiful, my son,’ Mumsy, don’t you rip on me, get the fuck off. ‘There’s no escape for you, Martin, you keep forgetting this minor fact, the wound has never healed on Edina’s face. Her mouth was ripped, she called me asking what to do, because I’m your mother and if I don’t know you, then there’s no one on this earth who does. There is no one, I said, and hang up. I saw Edina in front of me, standing in the hall with the red bakelite receiver in her hand, you had got it from the company. I went into the kitchen, put on a coffee, Edina was far away.’ Mumsy, stop it. ‘No, Martin, you’ll listen this time. By the time the coffee boiled down, Edina was standing in the door, I knew it was her because she gave two short rings, as we used to, as she had learnt it. Your father used to ring like that, when he did so for the last time he had long had that German whore, and I said to myself I wouldn’t open the door even if I died of it. Now God himself could knock. You could’ve learnt from that. One cannot escape, in the end, you can stand there with a stupid face all smartened up, and God is just laughing loudly.’

‘In the morning, Edina was lying there curled up, with her feet drawn under herself. When I woke her up she began to swear she would scratch the eyes of that bitch who took you away from her, because of whom her face was swollen and purple. Martin, you know, I found her the most beautiful then. You have been pampered by life, all women whom you’ve made fall in love with you loved you till they all went to the dogs.’ You’re wrong, Mumsy, Marla doesn’t love me. ‘You’re only imagining Marla, Martin. Marla doesn’t exist. There is no such spice of life, your Grandfather’s stupid fallacies about lovers and wives, but these things only exist in your head. I am here, Martin, and your Grandfather is here, too, your father and Edina. Szofka only exists, too, when you look into the mirror. Szofka forgives you, only you cannot forgive yourself, because you’re just as filthy as the others, not a bit better, not even purer.’

‘Picture this, Martin, you’re a liar, a weakling and a coward, for a little fuck you’d lie the heavens down, and you don’t give a damn whom it hurts.’ But why would it hurt anybody, Mumsy? There is nothing outside of me, there is no one inside me either, there is only you and me, we only imagine father, when he lies that he’s been to playing soccer, we imagine Szofka and Edina, the woman who forgives and the woman who’s wearing my marks on her body. Marla is silent. Marla is sacred. The most beautiful woman to whom I’d never have lied if she hadn’t force me to. ‘Martin, Marla is you.’ The girl with the fuzzy lap, almond blossom.

Mumsy, I’m burying Marla tomorrow into the earth, into the mud, forgive me. The belief and the disgrace that maybe I have nothing eternal inside me, which, just like Marla’s nails, keeps growing, it is full of life, like Marla’s hair. But I have nothing. All is silent, Mumsy, forgive me for lying to You, even if you knew, how could you not know, Marla is just dying, and I cannot bury her, Marla’s tender, almond-eyed face is covered in loosened bandages, and I disappear in that, even if Szofka is the only woman, Marla has killed me, Mumsy, sometimes I wish your womb dried up.

Nude

The body is heaving slowly. A weight on the heart, every breath is for easing it, pushing out the suffocating particles from the flow. Deadlines, questions and bills are mere biology now. The pillow and the left hand beneath the head, gazing into the light, not feeling numb. Letting the wrists fall gently, might as well move, the other one resting on the hip, comfortable angles. Knees slightly drawn up. Sleeping. Silence, moss is rustling among the Buda mountains, Marla is drawing the garage door loudly, she will slightly lean before entering. I must go back for the photos, she thinks to herself, because it’s still better if she fetches them than letting them to be found in the rubbish years later by foreigners. The unknown, yellowish picture in the attic, how could it fly up there? Of course it was explained with the bombings, the force of the explosion had pushed it up there, and the coincidences had somehow arranged that Grandpa and Grandma ended up in the same attic. It could be beautiful, watching them fly, she thinks, and switches on the light. In the garage forgotten tools and machines, a table, a box was put above it for the nails years ago. The tenners, the sixers, and the female screws separately.

With car keys in hand, she’s still thinking about the house, the newly varnished parquet, the smell of paint. The flat had a clean smell, as if it used to be dirty before, but not at all, after the elders everything just has to be cleaned up. They kept repeating this all the time. In the corners mould has appeared, the gas heater is clicking, and all those walls leave too little space for humans. She sees in front of her the dining table, the compulsive family occasions always taught her a lot, she would prepare perfectly, especially for her own roles. Maybe this exactly was the problem here, maybe the roles are not clearly cast among all those grinning adults, the girls limping uncertainly – until they become big with child they are not actually family yet. Then they can give advice or take it, don’t pick it up, it will stop crying anyway. Testing the spaces, who can dominate the others and to what extent, how much can be carved off them. Based on age or gender. When the body awakens to its own consciousness, everything coming from outside is like coming from underwater, how much a new body can remember of all this? All those dialogues eavesdropped from the bathtub, when she used to wash her hair the tiles and the pipes were carrying the sounds, they got distorted into inarticulate noises, maybe this is all that remains from these talks, too. What remains of the newspapers under the carved off paint or the old fillings?

The window was taken out without any cracks along with the frame, on the new one there’re bars, and through those you can look far. She’s thinking of Grandpa and Grandma, now that dusk comes so early, they are standing in the window, it’s an evening ritual, Grandpa is holding Grandma’s shoulder, they are watching the city opening up to their drawing room, all the lights are familiar, parting the houses below here and there, buildings, there is the Bazilika, look. The flat is darkish now, only the little lamp is on. I’ve chosen the most beautiful woman. Grandma laughs, turns to him and squeezes Grandpa’s side. Kisses him slowly. The grey curls move, as if swept by the wind, but it’s only Grandpa leaning on Grandma again and again. They peel off each other the hesitating arms, Grandpa moves, Grandma waves back. You’ve got too many clothes on, mademoiselle, he says naughtily, winks, Grandma’s eyes are glowing. The lights outside curl a bit up together, from the other bank Pest is mirroring the old eyes back, that’s not the sky, the black pupils are expanding. The body doesn’t move anymore like it used to, or like it should, he slowly helps off the cardigan, Grandma helps with the belt. Then the buttons of the blouse are clumsy again, the fingers thick, they have grown huge in comparison with the tight holes, I’ve grown old, she laughs. Grandma is thinking of the pictures, the child’s face, the longish, egg-shaped forehead, the skull. What is it like to look for and find Grandpa in that, hoping that the bone is eternal, that there might be something eternal in humans, despite all those years, all those mornings, waiting in front of the bathroom, even if it all becomes mere dust, it still can blend with dignity. His countenance is clear, I’ve fallen in love with its curiosity, but she doesn’t confess it. It should be written down before it is too late.

He’s leading his wife to the bed, they are pacing slowly, carefully, the knee doesn’t bend easily, at certain moves it even hurts. But now it’s throbbing, maybe more silently then before, how much sweeter music this is, the woman thinks while her husband sits her next to himself onto the bed. Upon the bra a combie, the old silk one, the little lamp makes it look hazy, but it’s the most beautiful fleshly colour, according to the old fashion a quality brand. They undress separately. The two bodies are bending next to each other, there is nothing erotic, nothing wild about this, and it’s still the most passionate and the most human of all, the way these two are now undressing for each other. They are not greedy, not tearing anything off, this is how the textile becomes sacred and the body becomes sacred, too, one and the other, bending down, as if onto an altar. The two people are now the closest to each other. There’s no fear, because there is only closeness, there is no envy, only beauty, and there is no foreignness, only peace. The man is resting, the socks crawling out of the depth of the trousers, it’s not easy either. The smells get more intensive, the Buda street is silent, slowly all the neighbours get home, put the supper on the heat, check the homework. The woman’s arms are hardly moving, loosening the skirt, steps out of it, it slips down slowly, she cannot wriggle out of the combie, the man stands in front of her, helps it off. He helps her to undress, as if helping her to bathe, not peeping at her breasts. Those are shrinked, of course, the wrinkles make them formless and they also hang, but she doesn’t hide them. No shyness, no shame. You know it like your own. The man nods, now comes the shirt, some other time he would take on the pyjama bottom. Now he’s undressing. Her tights reach up the thighs. She unbuttons the garters, gently rolling them down on her legs. She puts them on the bedside, too, beside the skirt and the blouse, next to the man’s shirt and folded up trousers. The terry cloth bathrobes are lying unconsciously around. They are panting, the woman sitting in langerie, the man in his underwear. The body covered with spots, freckles and warts, their cells have grown old together. The man’s back is full of ditches like gaps in the dried up earth, the woman’s is like a softer loess soil. The body is heaving slowly. A weight on the heart, every breath is for easing it. All those years cannot be condensed. In the end, it can be summed up on a bedside, the way they are sitting there next to each other, desiring each other as never before. Don’t switch off the little lamp, I want to see you, Grandma says.

From the garage, stairs lead up to the house, the rooms are empty, she goes to the bedroom. Watching, the body is heaving slowly. A weight on the heart, every breath is for easing it, pushing out all the particles from the flow. Deadlines, questions and bills are mere biology now. The pillow and the left hand beneath the head, gazing into the light, not feeling numb. Letting the wrists fall gently, might as well move, the other one resting on the hips, comfortable angles. Knees slightly drawn up. The Comb Man is sleeping. Marla is sitting on the bedside and begins to undress.

(Eszter Ureczky)

Csobánka Zsuzsa: Belém az ujját

Budapest: JAK/Prae.hu, 2011

If someone were to venture to say anything they would start by stating that the stones will again be nice and white for 2011. St Matthias’s Church may be dark, but it is nevertheless possible to go round it and its towers are visible to the unaided eye. The walls need a fresh coat of whitewash, Edith thinks to herself, as she looks into the dark. The rafters are also being reinforced so they will not crack under the weight of roof tiles. The rose window was still there a week ago—maybe it does not need refurbishing, it will put up with carpet bombing. A strong castle—a Feste Burg. My God, what a lot of rubble there is!

Cellars which have collapsed under houses, and all Father will say, again and again, 50 years later, is that I should stay a coward and get used to my face. He will be conceived not long from now, World War II is slowly coming to an end; Mother, heading home, is barely nine years old but muscular and conceals demonic forces. This is where, in a couple of years, she will meet Father, who is hiding underwater. Out of anguish and terror they become entwined into one; separately each is lacking for life. He is 18 and his gaze is wavering, whereas she is more woman than girl and will be 30 before long, but she still falls madly in love with the burbler. Mother, who has been painting a picture ever since, says that eventually there will be a big gateway on it, she can already visualise it, the perspective from ground up with the clouds and sky up above. Only because I was still a child. She has been on the point of painting it ever since, but perhaps now she will really set to it as for years all she has done is stretch the canvas, the material will take it, and maybe even the sun will begin to shine between the clouds, the gate will be converted into a door, budging and taking in. It would be a crime to wait for that.

There is nothing beyond the gate. Mother did not speak, merely slapped my cheeks when, as a joke, I set fire to a classmate’s hair. It had seemed a good idea at the time as I had already prepared the flies and they were waiting the next instalment. We looked through the magnifying lens at how the articulated legs thawed, the others standing around me and eagerly watching. Éva shouted ‘Look it’s about to fly away!’ Which was why I had plucked off their wings. Because love is madness, it was no use my explaining to Mother that Éva had dobbed on me to the teacher and I had to have her punished for doing so. She knew I was lying. If not then love and hatred were again touching on each other, and that was the worst thing which could happen to me. I stood by her, but Mother turned away. I’m not interested in you, she turned the tap on ostentatiously and washed the vegetables, but I yelled at her: Mummy, listen. That was the first time she had smacked me on the face.

The way Father told it there was a ring on Edith’s doorbell in the evening. Edith was my grandmother, and in her flat on Üllői Avenue in her haste she had slipped into court shoes as she could not find any others all of a sudden. She had draped a shawl over her coat and reached for her hat when she nevertheless broke into a smile: ‘Really, what for, for heaven’s sake’. She had learned a few years before that there is no such thing as human dignity. The Arrow-Crosser had visited every week so that she would not be taken away like the others. Nothing is for free in life, that she had learned, as well as the fact that there is such a thing as evil. When he had knocked on the door the first time there were still two of them, outside as well as inside: Edith and her spouse, my grandfather Jakob, and the Arrow-Crossers. One of them was a youngster, the other a gaunt fellow in his fifties who limped and said very little. His words stuttered out harshly; neither man found refuge in Edith’s blue eyes. They had come for Jakob, who (if it’s possible for a person to carry out that sort of absurdity) was prepared for every eventuality but did not dare stroke his wife’s belly. Father, with his pint-sized body, hovered or floated in silence. The Arrow-Cross shaver went back out of the door; he cannot have been more than 16, and Edith had lovely clear eyes which not much later were dead to all further looks because when, a couple of hours later, he knocked on the door again she knew what was going to come next. Edith cursed God and forget his very name. She damned the lad by singing a folk tune about the Danube as she slowly unbuttoned her shirt.

I’ll beat the stuffing out of you, squeaked the youth with all the arrogance of a 16-year-old’s bumptiousness in his voice, whereas Edith, for her part, was unwilling to peal off her petticoat, which had started to fray here and there along the seams. The shaver ripped off the straps; her shoulders by then were little more than sticks. ‘God, you would have to be made of sandpaper to be worth anything.’ If pain could be felt. The buttons holding the cotton stocking popped open, but Edith did not hear that. She hummed the folk song ‘My sorrow I’ll take it to the mill and have it ground there’. The slip stayed on as did the Arrow-Crosser’s uniform. The flagstones of the bedsit flat were cold; he made Edith kneel on them in order to part her bottom. From then on they alternated: ‘Let’s get cracking, my wee bint, let’s see you hop! Don’t even dream of it! No need to worry your head about getting a proper bastard! If your shoes are torn I’ll get you new ones,’ he growled. ‘A Yid whore is only good for screwing the arse off and it doesn’t put a bun in the oven—you’ll be taken off in a railway wagon before that. You’d deserve it too.’ Edith sang, whereat he socked her on the jaw; ‘I’ll slit your throat if I hear another peep from you!’

The shop assistant at the milliner’s shop insisted that she could bring Edith a suitable pair of shoes from nearby, a sort that film actresses themselves wore, genuine leather. Your ankles are heaps more graceful than even a star’s like Katalin Karády. It has a buckle on the instep, now Edith is looking at it, thinking how hard she laughed then. She slowly unbuckles it while the youth pokes her in the back. Get on with it! Edith is mute, like the mill. She can hear the creaking, the sound of a carpet bomb, the sound of her cotton socks sliding on the flagstones of the bedsit floor, grazing her knee. But in truth there is only the St Matthias Church rising opposite, with the cracked rafters, the rubble, and between it and me the water streaming from my eyes, so strongly am I looking.

No need for the big shot to call out; there was a soldier for every prisoner. The youth had finally left Edith on the quay, the squaddies lined up behind her. Behind the squaddies a barbed-wire fence. ‘Quick turn, all eyes towards the Danube.’ Edith quietly started humming again. Father was a tiny barge floating in her belly; Grandmother didn’t dare touch her belly, thinking that this child was not going to know what lies beyond the water, what does it take away, where does it flow. All I will tell him about is estuaries, and Edith talks to herself about the way the delta discharges into the Black Sea and the river is finally let go. There is no gripping at it, no dry land anywhere; the Danube is able to breathe again.

There is shooting, Edith topples into the Danube. Slowly, the way she had learned by eye in the mirror, the body splashing with a subdued plop into the Danube, with blood oozing profusely into the water. The fish gather around her, looking at her feet, which have no shoes on them, the soldier-boys leave on the quayside all the shoes they have ordered people to take off; the shaver spits on them too, cursing mightily: ‘Smelly-shoed-degenerates!’ Months later the river floods and those living in houses along the quayside are shaken to see them: ‘So everything is disposable,’ that is the way they thought, God is cruel and grotesque to play into the hands of the Arrow-Crossers because here, on the quayside, forgetfulness is a sin, and it occurs to them that we too are sinners. Yet the shoes stick strongly to stone; only the laces gradually loosen by the next January. First of all it is just mud which gets in and the brown leather dries up, the black ornaments that a cobbler once dreamed up. Neither the sales assistant’s nor Karády’s voice can be heard now, the high uppers wrinkle as if they were snarling lopsidedly. At the next full moon the tiny sea-snails and barnacles squat in the tips of the shoes, taking up abode in the glued inner cavities where a foot once drummed excitedly.

The feet have grown disproportionately large; that is what Edith thinks of while she hovers. The feet have grown disproportionately large, Edith, think of that while you hover, the calves had wasted away to the width of a B5 pencil, whereas the knees were like huge balls (‘Your calves have wasted away to the width of a B5 pencil, whereas your knees are like huge balls. Float!’). She was knock-kneed and had to stand straddle-legged so that the knees would not hurt and knock together, and Father should not cluck either amid the wild ducks on reaching the riverbank the morning of the next day. There is the same movement in Father’s gaze, barges knocking together on the river. ‘The train is taking me,’ she starts to hum the melody, ‘I’ll go after you…,’ but Grandmother does not complete it. Her thighs remain a secret. The cotton stockings ripped off the wizened skin by Boráros Square, just beside the Pest end of Petőfi Bridge, there no longer being anything by which her body might swell them so it let go. In the Lágymányos District, at the Buda end of the bridge, the coat was also left behind, and in the Free Port area on Csepel Island there was only a slip left to cover her body. Grandma is floating underwater, I have hummed it ever since; legend has it that she should have come to life somehow, but everything is different.

It is impossible to bear affection in hatred. Nor can I have any affection for either man or God who leaves Edith to plunge into the river and clutch her hollowed body on to the waterweed, wishing to feel the prickly undergrowth from close at hand, those innumerable tiny crabs and sea-snails; wishing to see Jakob’s face in the fish scales as if she were looking at me later on, looking into my eyes. Then let her slowly, as she had once unbuttoned her blouse, let her grow feathers, for down to appear in the deep pits of the eyes, for Edith to swim irrespectively in the Freeport, Arbeit macht frei, her mouth is frothing but she cries out, ‘It is a lie, it does not set one free, it does not redeem one.’ Father can hear that. Father is with Edith but the brain is like a sieve when it comes to remembering the nine months, along with the sea-snails, the green vegetation and the wild ducks.

I live in a way that the lower I reach in the river the more lies there are in me. Father is in the habit of saying ‘It’s not a lie, you only want to live, and to do that you have to lie.’ Forget the stench of burnt hair, give your heart an airing, tear away from Edith’s body as if she really were my grandmother, a woman who has turned into a wild duck with my father in her belly. They swim in silence; underwater it is silent—that is where they conceal themselves. But Edith grows fond of the waterweed, death, my boy, is madness, and love is also madness. And she hangs on while I pluck off the flies’ wings, the Danube stretches from the Black Forest to the Black Sea. I have no mercy in me, no kindness.

In 1944–45 countless hundreds of Hungarian Jews were shot into the Danube by militiamen of the Hungarian Arrow-Cross Party. In the course of the mass executions victims were forced to stand in line by the Danube and shot in the back of the head. Today there is a monument—sixty pairs of shoes made of iron—on the Pest side of the Danube Promenade to commemorate the victims.

(Tim Wilkinson)